As I walk in, a student is showing him stone tools, lifting them one by one from a zip-lock bag. Fereydoun Biglari, archaeologist and head of the National Museum’s Palaeolithic Department, has a slender frame and a goatee.

He wears a suit, as is typical of Iranian offices, and his room has a humble aura – museum brochures, journals and booklets on a shelf, a wooden desk with computer – that brings to mind Iranian professors I’ve visited before. A love of science or literature may not bring worldly rewards.

I tell him it was once my dream to be an archaeologist in Iran but that my parents didn’t let me. He laughs, and says with a calm certainty, “They did the right thing."

Alongside museum director, Mahnaz Gorji, Fereydoun Biglari was the main force behind the National Museum’s recent exhibition Evidence for Two Hundred Thousand Years of Human-Animal Bonds in Iran, which ran in Tehran from August to October.

Among the 350 exhibits was the 200,000-year-old jaw of an extinct bear (ursus deningeri) found at Darband cave in Roudbar, Gilan province, in northern Iran by the Caspian sea. The cave is a “lower Palaeolithic" site, which means it dates from the early part of the Palaeolithic period that stretched from 2,500,000 years ago to 12,000 years ago, when humans or their forerunners used tools but had not developed sophisticated art or religious practice.

- Palaeolithic age 2.5 million years ago to 12,000 years ago

- Lower Palaeolithic: 2.5 million to 200,000 years ago

- Middle Palaeolithic: 200,000 to 45,000 years ago

- Upper: Palaeolithic: 45,000 to 12,000 years ago

Biglari led the team that excavated Darband cave more than two years ago. Previously, it was assumed that the bear had lived only in regions between western Europe and the Caucasus mountains. The bones were dated in France – a country with which Biglari regularly collaborates as co-director of a joint archaeological project with the University of Bordeaux – using the Uranium series (U-series) dating method.

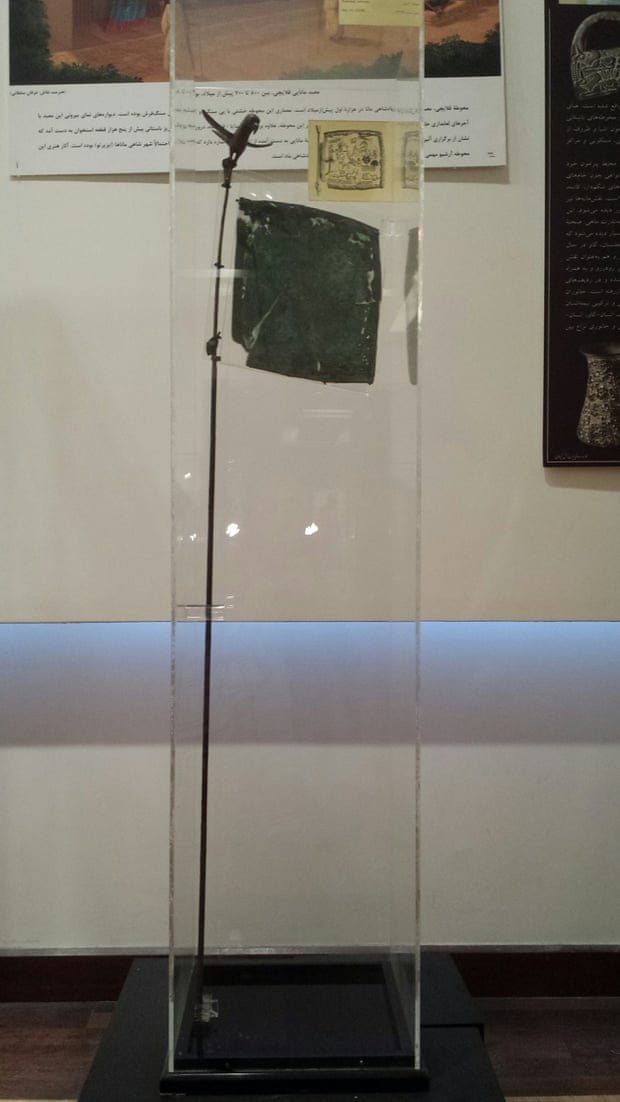

Far more recent than the bear’s jaw, and more instantly reflecting humans’ co-existence with other animals, were the exhibition’s miniature paintings of the Safavid era (1501-1736), 19th-century gilded birds from Isfahan, and a magnificent 19th century Qajar book cover featuring mythical creatures including a horse-man and a lion-bird.

I was delighted to find a 16th-century copy of Marvels of Things Created and Miraculous Aspects of Things Existing, a book by Al-Qazwini, the 13th-century astronomer and geographer. The work is partly fiction, partly science, a whimsical chronicle of real and imaginary species, and this copy had never been previously displayed.

Also open to public view for the first time were tooth ornaments worn by humans from 35,000 to 30,000 years ago (during the upper Palaeolithic period) excavated at Yafteh cave, Lorestan province, western Iran. Tear shaped and fashioned from the teeth of wild deer, their rarity suggests they were worn to denote high status.

I ask Biglari about the process of selecting items and setting them up within the exhibition floor. “Like most well-established museums, the National Museum of Iran has extensive items in storage," he says. “It was a matter of selecting those that helped tell our story. They were also vetted by our restoration team, as some objects were too fragile for display."

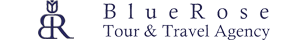

One such item appeared to be a third-millennium BC copper flag from Shahdad, Kerman, southern Iran, featuring a man and a woman facing each other.

In the end, the flag was added to the exhibition, and seeing it up close was an experience of its own. The delicate bird at the edge of the flag pole seems at first like a child’s doodle, as do the intricate details of humans, animals and trees. This simplicity is somehow profound: over 4000 years ago lived men who saw themselves at one with their natural surroundings. How drastically things have changed.

Other items I went to see again and again included a stone figurine of a boar from the 7th-millennium BC, found at Tape Sarab, Kermanshah. There were grander figurines on display, but the boar was so full of character and carved to the finest detail – despite its tiny size, perhaps a third of my index finger – that one could almost imagine it running out of the glass case.

Biglari explains a theme of humans and non-human animals in coexistence. Although man hunted for food and sport and clothing, and was a creature who could dominate landscapes, a delicate balance did not allow for mass species extinction. “In the past century, we have seen that balance completely torn apart," Biglari tells me. “With this exhibition, we hope to begin a discussion on the path that we have taken."

In her introduction to the exhibition brochure, Mahnaz Gorji calls the exhibition a “warning bell". And if this is a bell, Biglari shakes it with vigour, reminding me that once in Iran, there lived lions and tigers.

Perhaps the bell will echo in all of us. I remember hearing from an old great uncle how he and his hunting entourage were attacked by a tiger. In Khuzestan, south-west Iran, where I grew up there are old women who still tell stories of the lions in the bush near the city, although neither the bush nor the lions exist today.

But Jane Dieulafoy, in her memoirs of excavating Susa in 1880, speaks of lions in Khuzestan and even added a photo. As a child, I leafed through her memoir and pictures perplexed at how the Khuzestan I knew could have once been home to lions.

The big cats are animals whose disappearance we know about: for instance, the critically endangered Asiatic cheetah featured on the jerseys of the Iranian National Football Team this past World Cup in Brazil. But there are many other, less well known species within Iran that are already gone or on the verge of disappearance.

“The Asiatic cheetah is present in public conversation, but for some reason, most probably to do with its looks, no-one speaks of the vultures of Iran, who are on a path to extinction," says Biglari, referring to gypaetus barbatus, often known as the bearded vulture.

This exhibition is all the more timely given vast environmental changes in Iran today. Rivers and lakes are drying up, farmland is turning into barren desert. Many mammals, birds and fish are becoming creatures of a bygone era.

Elizabeth Kolbert, the American journalist who has dealt extensively with environmental issues, writes in her book The Sixth Extinction that there is currently under way “an event of a similarly catastrophic nature" to the mass extinctions of the Cretaceous period (145 to 66 million years ago) that included the dinosaurs. Miles Silman, a researcher she speaks to, reminds me of Biglari: “In other kinds of human disturbances there were always spatial refugees. [But] Climate [change] affects everything." Simply put, there is nowhere left to run.

Those behind this exhibition at the National Museum believe the Iranian public needs a broader perspective on humans’ place in the wider world, and that such education can be helped by exposure to Iran’s strong past role in human migration, or to its having been home to Neanderthals, an extinct species closely related to humans that walked the earth from 250,000 to 40,000 years ago.

One of Biglari’s hopes is that such an exhibition will encourage the Iranian Heritage Organization to fund future Palaeolithic excavation. Sites in Kermanshah and Gilan have shown there is a much older history than currently understood just waiting to be revealed: “Gilan currently furnishes the most convincing evidence for the earliest evidence for the presence of hominins [humans and our immediate ancestors] in the Iranian plateau," writes Biglari.

Biglari himself has also been involved with efforts to excavate middle Palaeolithic sites in Kermanshah, such as Warkaini, where middle and upper Palaeolithic stone tools have been found. “Neanderthals lived in Kermanshah caves 85,000 to 40,000 years ago," reports the Iranian Centre for Archaeology and Bordeaux University, after an excavation project headed by Biglari.

While he and his team have not had the opportunity to excavate further in Darband cave, the ecological similarity between the west of Alborz mountains and the northern Caucasus where Neanderthal remains have been found encourages hope of further finds. In places such as Shanidar cave in Iraqi Kurdistan and Azykh cave in Azerbaijan bones attributed to Neanderthals have been excavated and studied. Biglari hopes that in coming years, more serious resources will be invested to pursue such scholarship in Iran.

Through our discussions, I get a glimpse of what goes on behind the scenes to bring such an exhibition to life. I ask him about the order of items showcased, as there sometimes seemed to me a lack of chronological coherency. He explains that some solid gold objects - including cups from the 1st or 2nd millennium BC, which are among the museum’s most valuable treasures – had to be displayed where there were in secure glass vaults.

“That affected the chronology of the stories we wanted to tell, but there was nothing we could do about it," he says. Biglari also regrets not translating exhibition posters from Farsi, since at the time of planning, there were few foreign tourists in Tehran. “As luck would have it, the situation improved and now we are seeing busloads of tourists, but all we had time for was an English brochure."

The question of tourism raises the issue of access to sites. Biglari disapproves of the Roudbar cave being open to visitors, dismayed by his own return there a few months after excavations ended. “For days, the team and I were going around collecting juice and water bottles. We simply don’t have the infrastructure to allow in tourists without destroying what is there."

This brings us to looting. With its archaeological treasures, historic sites all over Iran are vulnerable, especially with locals digging and selling to illegal collectors. “When we started at Darband cave," says Biglari with a grin, “the villagers openly and kindly informed us that we should not bother, there was nothing there." When I mention rampant looting at Susa, he says “Khuzestan is tragic story" and shakes his head in bewilderment.

In so many ways, the world we know today is so unlike the world opened up by the exhibition in which we sense the interconnectedness felt with their surroundings by the creators of bowls, figurines, incense burners or books. Perhaps what we takes away most is the comfort with which man seems to have once spoken of other beings, and sense that there is no clear boundary between us and the rest of the animal kingdom.

Although it may never influence policy nationally or internationally, and though we may continue to plunder until there is nothing left, the exhibition depicts where we began and how we got here. Fereydoun Biglari is out to show us Iran in a way we have never seen before and to remind us that we must save other creatures if we are not to lose ourselves.